|

For European artists, the idea of silence was purifying and enriching, but composers like Eimert were already questioning the purpose of this direction in the 50′s and 60′s, with many others feeling the same which perhaps explains the proliferation of serial compositions with distorted and wrecked “voices”, ie. Babbit’s Philomel (1964), Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge (1955-6) Nono’sIl Canto Sospeso (1955-56).

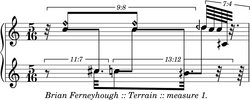

With the advent of computers and programmed algorhithmic composition, this depersonalization extended further, allowing composers to grapple with massive amounts of information that could be bent and manipulated to compositional frameworks. At this point, the computer became capable of composing more purifying, enriching serial experiences than a composer with limited time and energy could accomplish. Had serial music’s destructive seeds taken root? Detachment continues in postmodern music, but we see afterwards a return to expression, representation and, in the 80′s onward, a new sincerity towards artistic practice. So, broadly speaking, is atonality and serialism a strange footnote in music history (like the ars subtilior in the 14th/15th century)? Do we continue to inhabit the “era of the sonata form”?

0 Comments

Gabriel Fauré: 9 Préludes for solo piano, Op. 103 (1910)

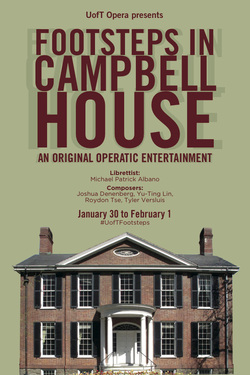

Gabriel Fauré: Theme and Variations (1895?) Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata in C major "Reliquie", D. 840 (1826) Boris Lyatoshynsky: Five Preludes for solo piano (1943) J.S. Bach: Toccata in C minor, BWV 911 Marin Marais: Sonnerie de Sainte Geneviève du Mont-de-Paris Girolamo Frescobaldi: Fiori Musicali (Missa della Madonna) (1635) Alexander Mosolov: String Quartet No. 1 in A minor (1926) Guillaume Dufay: Ave Regina Caelorum a 4 Alonso Lobo: Versa est in lucta cithara mea Anton Webern: Drei Lieder  Writing good opera is like making good curry- all the regular ingredients need to be balanced out but you also need that little bit of off-the-recipe spice to perfect the creation. Opera, like curry, is easy to ruin as well: over-intellectualize your recipe or be flippant with your ingredients, and you have an entire saucepan of inedible reddish-brown goo that only your most polite dinner guests would entertain. After some serious recipe-adjusting on my behalf (mostly involving re-measuring portions of dramatic timing), U of T's collaborative opera Footsteps in Campbell House is almost ready to be served at Toronto's historical Campbell House (160 Queen Street W). The opera will be performed 5 times by U of T's Opera Division. Performances are limited to 35 guests, since the opera will take place in different rooms within the beautiful historical house. Foosteps in Campbell House Libretto by Michael Albano Music by Joshua Denenberg, Yu-Ting Lin, Royden Tse and Tyler Versluis Performance dates: January 30th, 2015, 2:00PM January 30th, 2015, 8:00PM January 31st, 2015, 2:00PM January 31st, 2015, 8:00PM February 1, 2015, 2:00PM Tickets: $20 All performances at Campbell House, 160 Queen Street W (near the Four Seasons Centre, Subway exit: Osgoode Station) Book in advance to secure spot! Performances limited to 35 people per performance. Call the Campbell House Box Office: #416.597.0227 ext.2 Disclaimer The following text is a summary of Eduardo De la Fuente's essay, "Prophet and Priest, Ascetic and Mystic: Towards a Cultural Sociology of the Twentieth Century Composer", published in Philosophical and Cultural Theories of Music (2010), ed. Eduardo De La Fuente and Peter Murphy.

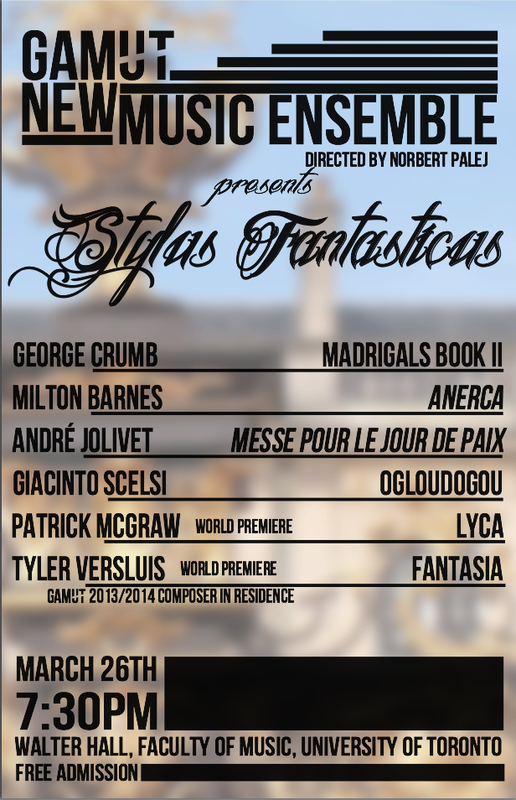

European Modernist culture’s longest lasting obsession has been the pursuit of an “aesthetic” salvation, primarily a result of Modernism’s break with institutional Christianity and the elevation of the Artist-as-Priest. Art as religion solidified in the 20th century as Wagner’s theoretical writings espoused with the writings of various modernist philosophers, and a revived interest in the Apollonion, objective Kunstreligion of ancient Greece. Max Weber suggested specifically that the 20th century composer resembled a religious professional, paving paths to aesthetic salvation based on their various rejections and affirmations of the world. These “professions” can be subdivided into four categories, the composer as prophet, priest, ascetic and mystic. Prophet: A person for whom the “conflict between empirical reality and his conception of the world as a meaningful totality […] produces the strongest tensions in the man’s inner life, as well as his external relationship to the world.” The prophet “discharges his internal pressure”, and their persona is marked by an unresolvable tension between their sacred duty/mission and the world. The prophet gains a mythical status and a swath of blind followers; they are charismatic and do not gain reward from the “field” or institution; their art is not commissioned or supported widely. Example give by De La Fuentes: Arnold Schoenberg Priest: The priest is specialized, with a vocational qualification and an aura of “fixed doctrine”. Their views, metaphysical or otherwise, are rationalized: their role is to make peace with the past and to ensure that their sacred activity is shared and maintained with the “laity”. The priest is utilitarian, valuing coherence, constraint and unity. They reject the aesthetics of “expression”, and Modernity; they are rooted in a pre-Romantic-era past. Example give by De La Fuentes: Igor Stravinsky Ascetic: The ascetic controls the demands of their inner-world; everything must be rationalized, not only elements perceived to be unorganized, but all elements perceived as expressive, spontaneous and purely conventional. The goal is “…supremacy of intellect over passion, the triumph of mind over physical instinct”.Example give by De La Fuentes: Pierre Boulez Mystic: The mystic’s primarily principle is to remain silent so that God may speak. Their action is minimized, which puts them in contrast with the ascetics, who prove themselves through action. Perhaps the mystic’s ultimate goal in their silence is to pursue the elements that lie beyond their own intentions. The mystic is irresponsible to himself, risking their reputation and state in order to achieve and overarching acceptance of all circumstance. Example give by De La Fuentes: John Cage  Last night I sat down with a few composer participants at the Atlantic Music Festival and engaged in some vocal improv for an hour or two. The session, led by composers Diana Sussman and Grace Ma, began with some light yoga warmup, then a "feeling out" of the space we were in- the sound of the air conditioning system, the humming of the fluorescent lights- followed by a period of adding our own sounds to the environment: humming, whistling, clapping, groans and murmurs. This warmup provided a period of relaxation where we could ease into the improvisation process, which was primarily vocal based. This type of improv was quite new to me- most of my experience with improv has been with piano or organ, or with semi-improvised score based material. Improvising with no exterior guidance or instrumental extension is both strange and surprisingly natural. Strange for someone immersed in the Western classical tradition of notation-based music, and natural from an almost broadly human standpoint- a community of music-making that requires no training or experience, just a lack of ego and self-consciousness. Hear a recording of our last improv HERE  The 2014 ARRAYmusic Young Composer's workshop is under way! This year us four young composers are under the mentorship of Vancouver-based composer Rodney Sharman, who brings with him a vast array of compositional knowledge from various forefronts of contemporary music, and Rick Sacks, artistic director of ARRAYmusic. Every year the instrumentation for the Young Composers Workshop varies, and this year the instrumentation has settled on 'cello (Rachel Mercer), clarinet (Colleen Cook) and percussion (David Schotzko). Click here to listen to a sneak preview of what I'm working on at the 2014 ARRAYmusic Young Composers Workshop. So far the the workshop has been rewarding and also challenging, as I find myself grappling with a large collection of artistic talent and possibility. The most graceful element of the workshop, is, of course, the extensive amount of TIME we get with such awesome musicians- time to experiment, collaborate, extrapolate and elaborate... anything we can and must do! Certainly countercultural to the limited rehearsal times, hyper-efficiency and overproduction that dominates most new music structures and organizations these days. You can hear the final product of this workshop on May 31st, at Array Space, 3PM. More info here On March 26th, University of Toronto's gamUT new music ensemble will perform my new piece, Fantasia, in fulfillment of my residency with this group. The concert will also premiere a piece by Toronto composer, Patrick McGraw.

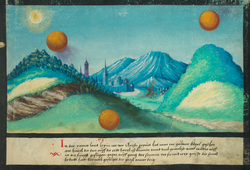

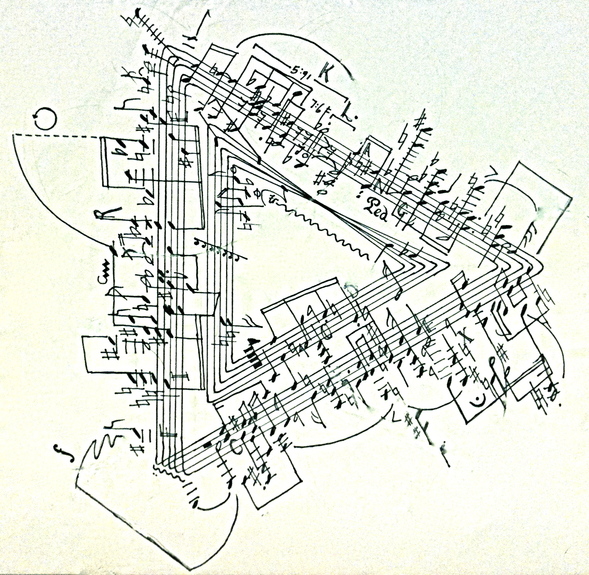

"Polyphony organizes differences in a deconstructive way; unlike homophony, where voices blend into perceptual unities, polyphony poses the question, ‘does difference function as difference?’ (Mahnkopf, 2002, p. 39). The functioning of difference as difference affects not only the musical material itself but also the manner in which the listener perceives the material. According to Mahnkopf, polyphony forces the listener towards two phenomenological states: positively, the listener enters a state of diagonal listening as a form of ‘mental compromise’, because the ear cannot simultaneously grasp a synchronic layering and diachronic unfolding of such detail and complexity. Negatively, the listener experiences an apperceptive overload where the ear discovers a quality of ‘too-muchness’, an excess of musical relationships that reach sublime proportions. And like the classical sublime, apperceptive overload reveals the limits of the subject’s capacities, a limit which both reasserts the power and domain of both the interiority of subject and the externality of nature, its other.” — Aspect and Ascription in the Music of Mathias Spahlinger, Brian Kane. Published in Contemporary Music Review 27(6): 595-610, ©2008 Taylor & Francis.  Intentionality is an important part of composed music- but I also realize that there are large portions of musical material that flowed from a hidden source- that is, material whose presence cannot be justified through empirical methods. The idea of musical development is, on a basic level, an empirical process because the development springs forth from that which is already “experienced”, or material heard earlier in the piece. On the other hand, there is the material that falls outside of the empirical process, the “dark matter” which marks its presence through its “unknownness” but justifies its presence through mysterious and ultimately mystical means. One of my professor’s describes these ideas (klangs, motives,chords, etc.) as “sphinxes”, carriers of hidden knowledge whose secrets remain profound but very much shrouded. A good composer’s music is wholly intentional- they are able, through mystical processes to make their “sphinxes” feel equally as important as their empirical material. Besides the obvious, some composer that effectively utilized the mystical include J.S. and C.P.E. Bach, Schumann, Sibelius, Prokofiev, Dufay, Mozart. “It is conscious plagiarism that demonstrates invention: we are so taken with what someone else did that we set out to do likewise. Yet prospects of shameful exposure are such that we disguise to a point of opposition; then the song becomes ours. No one suspects. It’s unconscious stealing that’s dangerous.” — Ned Rorem, Paris Diary (Summer 1951)

|

AuthorTyler Versluis is a composer and pianist. Archives

October 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed